[This is Part 2 of 3. Part 1 is here. Part 3 is here.]

Write, write, write

I spent about six months blogging regularly. I’ve never had a super structured approach to blogging, so I just end up writing about whatever’s on my mind. Continue reading

There are 16 posts filed in Economics (this is page 2 of 2).

[This is Part 2 of 3. Part 1 is here. Part 3 is here.]

Write, write, write

I spent about six months blogging regularly. I’ve never had a super structured approach to blogging, so I just end up writing about whatever’s on my mind. Continue reading

@ModeledBehavior (the Twitter account for a group economics blog, ModeledBehavior.com) shared this on Friday night:

Because what we need right now are more labor market regulations http://nyti.ms/ivdMwq

Obviously, @ModeledBehavior was being sarcastic here, but the Connecticut legislators are totally serious. Their plan is to mandate that hourly employees in the services sector will be given one hour of sick time for every 40 hours they work. There’s a lot of good stuff here that illustrates how little politicians understand about economics.

Here were my replies (first, second) to @ModeledBehavior:

@ModeledBehavior New Wage = Old Wage – 2.5%. Or, for minimum wage employees: New Employment Rate (NER) = Old ER – 2.5%. #Winning #Recovery

@ModeledBehavior Total wages paid won’t change. It’s a mandate for service sector employers to withold 2.5% of pay in sick-pay savings acct.

What’s tricky about this sort of thing is that it sounds so nice. But it takes a lot of effort to really understand what this legislation would do, and what it means. This sounds really nice because hourly employees typically just have to call in sick and miss a paid work day when they’re not feeling well. Too many missed days and the employee’s job could be in danger. This way, they’ll still get paid for that day when they’re sick.

But not really. As I replied to @ModeledBehavior, one of two things would happen: either the employers would lower the hourly wages they pay or, for minimum wage employees, they’d simply hire fewer employees. I’ll break down each case below.

Before I go on, let me set up the analogy I’ll use for the rest of the post:

Tommy works at a grocery store and gets paid $10 an hour. The proposed legislation says the following to Tommy’s employer: “Tommy is going to work 40 hours this week, but you have to pay him for 41 in case he gets sick later. Just hold back that extra hour’s pay and bank it so he can use it when he needs it.”

Two possible results

Let’s say Tommy’s 40 hours of work is worth $400 to the employer ($10 per hour). The employer can afford to pay Tommy $400 for every 40 hours of actual work Tommy does. This new legislation says the employer has to give Tommy one hour of sick time for every 40 hours he works. This will happen one of two ways (remember the employer is not making any more money when Tommy is out sick – his revenue is the same, or possibly less since Tommy can’t help sell or bag stuff when he’s out sick):

New wage = old wage – 2.5%

This is the most likely, but it assumes Tommy is making more than minimum wage. We’ve already said the employer values Tommy’s 40 hours of productive work at $400. So, when Tommy bags groceries for 40 hours, that’s worth $400 to the employer’s store. If Tommy is out sick, he’s not bagging groceries and therefore isn’t adding value to the store. So, Tommy’s value doesn’t change – it’s still $400. Only now the employer has to pay Tommy for 41 hours of work. What to do? Reduce his hourly rate so that the total cost is still $400. If Tommy was getting paid $400 for 40 hours of work, the employer will simply continue paying Tommy $400, only now it’s for 41 hours (40 hours of productive work and one hour for the sick bank). Tommy’s hourly wage will drop from $10 to $9.75.

$400/40 = $10 per hour

$400/41 = $9.75 per hour

Will the employer actually reduce Tommy’s pay by $.25 an hour? Maybe. But it’s more likely that the employer would just reduce Tommy’s hours and hire another employee at $9.75 an hour. Eventually, he’d just cut Tommy and move the new guy up to 40 hours.

For minimum wage employees: New Employment Rate (NER) = Old ER – 2.5%

But what if the employee were already making the minimum wage? Let’s call him Ralph and say he’s also making $10 an hour to make things easy? (In Ralph’s universe, $10 an hour is minimum wage whereas in Tommy’s universe, $10 an hour was well above minimum wage.) The employer can’t reduce Ralph’s hourly rate because it’s already at the minimum, and he can’t hire a new guy to do the work at a lower hourly rate. What to do? The only thing to do is hire fewer people.

Let’s say this particular store had 100 Ralphs. Each Ralph is being paid $10 an hour, so each Ralph is worth $2400 for 40 hours of productive work. Together, all 100 Ralphs are worth $40,000 for 40 hours of productive work, so that’s what the employer pays all the Ralphs to do their work.

$10 per hour * 40 hours = $400

$400 * 100 Ralphs = $40,000

The new legislation dictates that each Ralph now has to get paid $410 for 40 hours of productive work (minimum wage of $10 an hour at a total of 41 hours). But we know the employer has only budgeted $40,000 for Ralphs, so he’ll be able to employ fewer Ralphs.

$40,000 budget / $410 per Ralph = 97.5 Ralphs

100 Ralphs – 97.5 Ralphs = 2.5 fewer Ralphs

2.5 is 2.5% of 100 Ralphs

So, the number of Ralphs employed dropped from 100 Ralphs to 97.5 Ralphs, which is a 2.5% decrease. Each Ralph will now be banking one hour of sick time for every 40 hours he works, but there will be 2.5 unemployed Ralphs.

But what about these other options?

I would expect people to respond to this by saying that these aren’t the only two options, and they’d be right. But the other options aren’t great either. Maybe I’ll cover some of those in a separate post. Here are a couple options that might be suggested for handling this wage increase (with my response in parenthesis):

What’s your point?

My point is that this legislation is a bad idea and it will ultimately hurt those who it is ostensibly trying to help. The original article talks about how other legislatures are considering similar legislation, and they’re looking to Connecticut to see how it works. This could negatively affect workers’ wages and even increase unemployment at a time when the labor force is already hurting.

Coda

I’ve been talking to some small business owners about this and I’m getting a better idea of how this sort of legislation impacts business owners in the real world (it’s not much different than what I’ve described here). I may follow up on this post if I get enough new information and insight in my research.

The latest Planet Money podcast–How Many Jobs Has Scott Walker Created?–was about whether government and politicians can actually create jobs. The Planet Money team focused on Wisconsin’s governor, Scott Walker, and rightly pointed out that his plan doesn’t seem to be creating jobs so much as allowing them to be created by local businesses. He’s mostly doing this via small tax incentives for companies who hire new employees (we’re talking like net $300 for the company for each new job created). They correctly concluded that this tiny amount of incentive has little to do with actually creating jobs–if a company is on the fence as to whether to hire new people, then a $300-per-person incentive might get them off the fence, but it’s only a useful incentive in marginal cases.

Wisconsin Is Open For Business

Then they moved on to Walker’s “Wisconsin Is Open For Business” slogan that he is using to try to entice companies to relocate to Wisconsin (image from here). Here are some excerpts I transcribed* from Chana Joffe-Walt‘s (CJW) interview with Scott Walker (SW):

CJW: Who specifically is going to be hiring because of your program?

SW: Catalyst Exhibits that was from Crystal Lake, Illinois… We gave them an incentive to come up to the state of Wisconsin. They get a two year reprieve from state income tax.

CJW: Is that creating jobs or is that just stealing jobs from some other state?

SW: …It’s moving jobs. We’re giving them an incentive to move to the state of Wisconsin.

CJW: You’re very aggressively promoting “Come to Wisconsin”, right? And that’s presumably jobs that would be created in other states nearby. So, there is some element of just taking them from other states and getting them for your state.

And here are some comments from Adam Davidson (AD):

AD: They focus a lot of attention on getting companies to move from some other state to their state.

AD: …that doesn’t make our national economy do better. That’s not adding jobs or creating new industries. It just moves the pieces around the chess board a little bit. And that doesn’t really make for an overall healthier economy.

AD: …there are ways to use the tax code to encourage short-term behavior for a small number of companies. But what the economists concluded was that really what government can do is long term. That’s where government has a shot at creating long-term job development.

So Chana and Adam are saying there’s no economic benefit (local or national) to incentivizing companies to relocate to Wisconsin. The problem is they’re assuming that “jobs” is a zero-sum game, and they’re conflating competition with thievery. (They’re also assuming the goal is full employment as opposed to full production, but that’s another subject for another time.)

The implication is that Wisconsin (via Scott Walker’s plan) would coerce or trick companies to move from their current state to Wisconsin because there isn’t actual benefit to them moving. Or maybe they’re saying there is a benefit, but only to the company itself and not to Wisconsin or to the economy (state or national). This is ridiculous.

Is there a benefit to the company?

What would it take for a company–let’s use a fake company called Novelty Oven Mitts (NOM) that sells novelty oven mitts (noms)–to uproot itself from its current state and move to Wisconsin? A two-year tax reprieve might help, but a viable company isn’t going to just up and move because “Two years with no tax?! That’s just too good to be true! Let’s go to Wisconsin, y’all!” They’re going to do a cost-benefit analysis that includes the two-year tax reprieve, but they’ll also look at the longer-term picture:

“Well, we’ll save $50,000 in taxes over two years if we move. But then we’ll be subject to Wisconsin’s normal tax system. How much will that cost or save us after the two years is up? What’s the cost of relocating this company? Will all of our employees move with us? How much will it cost to replace the employees who don’t move? How would that move affect our business? Would we lose customers? How many? What is each of those customers worth?”

Eventually, they’d have a ballpark range of numbers and they would use those numbers to make their decision to stay or move:

“We’ll save $50,000 in taxes the first two years, but it will cost us $10,000 more every year after that. And we’ll lose five employees who we’ll have to replace when we get up there. The cost just isn’t worth it. Thanks anyway, Wisconsin.”

Or

“We’ll save $50,000 in taxes the first two years, and we’ll save another $5,000 per year after that. We’ll lose two employees, but we think we can replace those easily in Wisconsin and it’ll cost about $10,000 to replace both of them. We’ll save money by moving to Wisconsin, and our customers don’t care where we knit their novelty oven mitts. Let’s go!”

So, if NOM decides to move from Illinois to Wisconsin, they must see some sort real benefit. But it’s possible that only NOM benefits from the move, and that neither the local Wisconsin economy nor the national economy benefit.

Are there national economic benefits when a company moves from state to state?

If NOM decides to move to Wisconsin, either they will save money and continue doing the same amount of business, or they’ll be able to operate cheaper and will therefore be able to do more business (assuming there is demand for their noms). In the first case, some of the savings will become profit, and some will be passed on to consumers as lower prices (consumer surplus). In the second case, more consumers will have access to NOM noms because they’ll be producing more noms with their newly found excess capital. NOM would either buy new equipment or hire new employees with the excess capital in order to boost production. Either way, consumers in the national economy benefit.**

Are there local economic benefits for Wisconsin when a company moves into the state?

It’s tough to say if Wisconsin’s economy will benefit from this program. Presumably, they would also have done a cost-benefit analysis to determine the benefit of offering a two-year tax reprieve for relocating companies:

“If we offer this two-year reprieve, it’ll cost us $50,000 in tax dollars. But we’ll have a new company in the state, hopefully they’ll hire some people and then when the two years is up, they’ll continue paying taxes at $25,000 a year. So after four years or so, we’ll be in the black with this deal.”

Of course, if Wisconsin continues to subsidize*** the new business (eg, by extending the reprieve), then the national economy would benefit at Wisconsin’s expense since NOM would be getting services paid for by other Wisconsin businesses and residents.

Is this stealing?

This is competition, not “stealing”. The states are competing for business, and Wisconsin is trying to undercut other states’ prices (of operating a business) to get more business. It’s good for the consumer and the national economy. And it’s probably good for Wisconsin’s economy in the long-run, too.

Notes:

* I transcribed this stuff manually, and I may have made mistakes. Most of the stuff I quoted comes from the 17:30 mark. As always, I encourage you to listen to the podcast for yourself.

** I’m making some assumptions here. Namely that if NOM moves to Wisconsin and is able to operate cheaper, but doesn’t translate some of this into consumer surplus (meaning they keep all the savings as profit), then another competitor will step in and undercut them to get a tasty piece of that profit pie. If no one else would do it, then at least we could count on Urban Outfitters to copy NOM’s noms and sell them cheaper.

*** I’m playing fast and loose with “subsidize” here. It’s technically not a subsidy because the government isn’t giving them money. But the government explicitly isn’t charging them money that it normally would. So it’s technically a tax incentive or tax break. Potato, potahto.

A while back, I wrote about the price differences between Redbox, Amazon and iTunes for renting movies. My friend Andy emailed me to point out that I had missed a pretty big component of Redbox’s pricing scheme: Late fees. This was a pretty big oversight since it’s obvious that there will always be some people who keep a movie for multiple days. So I’m going to revisit this to make a better comparison.

Amazon and iTunes both rent for a fixed price, and then the movie simply becomes unviewable 24 hours after the movie has been started. Redbox charges $1 for a DVD for the first day, but they also charge an additional dollar for each day after that. If you keep the DVD for 25 days or more, then you own it for $25.

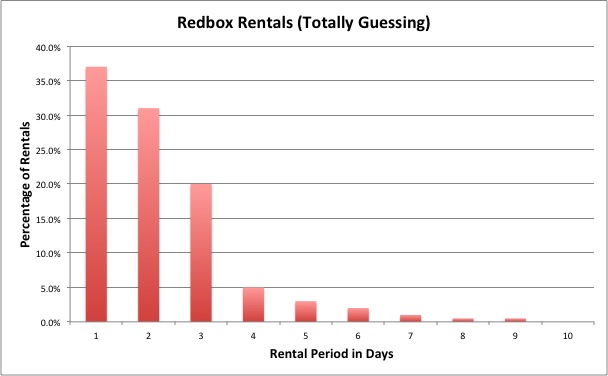

The time that people keep a Redbox DVD is probably distributed something like this*:

Redbox’s 10-Q for Q1 2011 says the Net revenue per rental was $2.20**. So the average renter keeps the DVD for 2.2 days and pays $2.34 (which is $2.20 plus tax in Gainesville).This is for all kiosk rentals, so it’s not just DVDs. But the point is that I’m guessing almost everyone will return the DVD in the first three days, but a few will hold onto it for several days.

So here are the price comparisons (from the average renter’s perspective) updated to account for typical rental times at Redbox kiosks:

Redbox – $2.34

Amazon – $3.99 (71% more than Redbox)

iTunes – $4.99 (113% more than Redbox)

These numbers make it more plausible that the difference in prices is mostly due to a “convenience premium”. Is it worth $1.65 to go to a Redbox kiosk instead of just streaming the movie to a TiVo or PC? For me it was, but for many it won’t be. Also, when I went to return “Waiting for Superman”, the kiosk was broken, which meant I had to go find another one. If I had known I’d have to make three trips to Redbox kiosks to save a couple bucks, I probably would’ve just rented the movie from Amazon.

iTunes is probably more expensive still because of the Apple brand and the additional convenience that an iTunes movie can be watched on Apple TV, a computer or synced to an iOS device (iPad, iPhone, iPod) and taken mobile.

* In case it’s not clear: I totally made this up based on the reported $2.20 “Net revenue per rental”. I’m assuming that people will either return the DVD in the first nine days, or they’ll keep it the full 25 days and end up buying it. I stopped the graph at 10 days to make it easy to read, and I assumed that one in 1,000 rentals would end up being bought after 25 days. Also, I’m being lazy here and not trying to tease out the actual DVD numbers since I’m using the $2.20 they reported, which includes Blu-ray and stuff.

** I’m a little confused by their terminology here. What I really want is the gross revenue per rental, but I can’t figure out what that is. I looked at the Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements, but I still can’t tell exactly what the “Net revenue per rental” number is. For Q1 2011, if I just take “Revenue” for the Redbox segment and divide by the “Total rentals”, I get $2.20. But this doesn’t work for Q1 2010 (I get $2.19, but they reported $2.16), so I don’t know exactly where that “Net revenue” number comes from. It seems like the gross number just isn’t being reported. The Redbox Wikipedia page claims (via the New York Times) $2 per transaction as of September 2009, so that makes me think the gross number is $2.20 and also makes me wonder why Coinstar is reporting it as a “Net” number. It’s also possible everyone else is misinterpretting the “Net” number as the gross per-rental number, so the gross per-rental number might be higher.

Last night, I rented “Waiting for ‘Superman’” from a Redbox kiosk near my house. This was my first Redbox experience.

I would normally just wait for it on Netflix Streaming, but I wanted to see the movie right now since it’s relevant to stuff I’ve been writing and discussing a lot lately. A friend had mentioned Redbox, and I had to go to the store anyway, so I checked to see if Amazon or iTunes could compete with the $1 Redbox price.

I ended up going with Redbox because I didn’t want to pay the premium being charged for rental by both Amazon Instant Video and iTunes. Here’s the breakdown:

Redbox – $1.06

Amazon – $3.99 (276% more than Redbox)

iTunes – $4.99 (371% more than Redbox)

What’s interesting is that it would seem that renting physical media would be more difficult and expensive than renting digital media. Someone has to service the kiosks, the physical media can be lost, stolen or damaged, etc. The rental terms are very similar – a 24-hour rental is standard. So why is it so much more expensive to rent from Amazon and iTunes than Redbox?

There could be a few things at work here:

What else could be behind the steep premium for renting movies online?

[Note: If you’re short on time, just click through and read the broken window fallacy Wikipedia page. It could change the way you think about economics and how you evaluate government policy. Also, I’ve put a couple disclaimers at the bottom of this post. I had to move them down there because it was just too much non-content leading the post.]

The latest episode of the Planet Money podcast – Why Japan Will Bounce Back – may have been misleading. A few weeks ago, I wrote the following tweet, but did not publish it (there are actually two drafts here – yes, I write drafts of tweets):

Well, apparently the economic stimulus bug has hit Japan! They’ll need to create hundreds of jobs to replace all that infrastructure!

What we call a disaster in Japan, Keynes would call phase one of a stimulus program.

I didn’t publish it because I was afraid it would be misread, and people would think I was making light of the devastation in Japan. I was really making light of the tunnel vision that many have regarding government’s ability to directly improve the economy through spending. Then, I heard the economist Planet Money booked to discuss the Japanese recovery flirting with the idea that Japan’s economy could see a net benefit from the disaster.

At first, they were just discussing economic resilience of industrialized countries. But they took it a little further from “Can Japan bounce back?” to:

Question from interviewer: Is it possible to come out with a net economic positive for Japan?

Economist: In terms of GDP and production flows you might be able to say that, except for the loss of wealth. You could’ve been using that same money – those same resources – for doing other things other than rebuilding.

In writing, this doesn’t seem quite so outlandish. But pretty much everything starting with “except for the loss of wealth” was said almost as a throwaway. It sounded like the economist thought the loss of wealth and redirection of resources would be insignificant relative to the overall “stimulus” provided to the rest of the economy. (At one point, he did compare Japan’s recovery to the economic recovery resulting from the stimulus in the States, so I know “stimulus” was on his mind when he gave the previous answer.)

I think what may have happened was the Planet Money team got caught up in the hook for their story: countries like Haiti and other impoverished countries do not bounce back catastrophe in the way that developed superpowers like Japan can. That’s true, but they got a little carried away and started veering towards the idea that the disaster could ultimately be a benefit to the Japanese economy.

Another quote (my emphasis added):

You could say, possibly over the next year or two, we’ll see some strong positive benefits including the construction of new highways, new railroads, new cell phone towers and telecommunications networks, new housing for people to replace the old stock. So we could end up with more modern, more productive, more efficient amount of capital out there than we have at the moment.

The problem is they are flirting with the broken window fallacy. Of course the result is “strong positive benefits” and newer infrastructure to “replace old stock”, but that doesn’t mean the Japanese economy will see a net improvement. In order to think that, we have to ignore all of the “old stock” that was lost. That infrastructure had value, and the new infrastructure will cost money to build. This is a net loss to Japan unless all of the infrastructure lost was essentially value-less before it was destroyed. All the old stuff was still there because it still had economic value, not because they just couldn’t get around to building more modern stuff. I’m sure there were some condemned buildings or whatever, but most of the stuff they lost was economically useful and so represents substantial economic loss.

I will note that they led with a discussion about how GDP doesn’t capture lost assets that were previously created or acquired. The example they gave was a bridge built 10 years ago: if the bridge disappears, GDP doesn’t take a hit even though there has been economic loss. So it’s possible that the quotes above were said in light of this idea that GDP could look better once Japan starts the recovery (it will). But it didn’t sound that way to me. It seemed like they acknowledged the shortcoming of the GDP calculation and then the rest of the conversation – including the quotes above – were about the economy in general (not in terms of GDP).

Ironically, most people would read this and think, “Duh. Of course there was a loss. All that stuff got wiped out.” In this case, common sense rules the day. If there is a building, and then the building is gone, that building has been lost. But economists sometimes like to get fancy and out think themselves. Hence the broken window fallacy mentioned earlier.

The disaster will result in economic benefits, just not to Japan as a whole. My guess is that geographically proximate countries will benefit as they will likely need to supply Japan with materials and goods while Japan bounces back. Competing economies will be able to sell more of their own goods (and possibly at higher prices) while Japan is offline. Even within Japan, smaller parts of the economy will benefit at a cost to the overall economy. The construction industry will surely benefit, as will other industries whose services will be required to rebuild. But the bottom line is that Japan lost a lot of its still-useful infrastructure, and that represents an economic loss. Estimates are that it will cost $100 billion to hundreds of billions of dollars for Japan to rebuild, and that’s a good estimate for how much wealth Japan has lost as a result of the disaster.

What do you think? Am I just seeing monsters under my bed?

Disclaimers