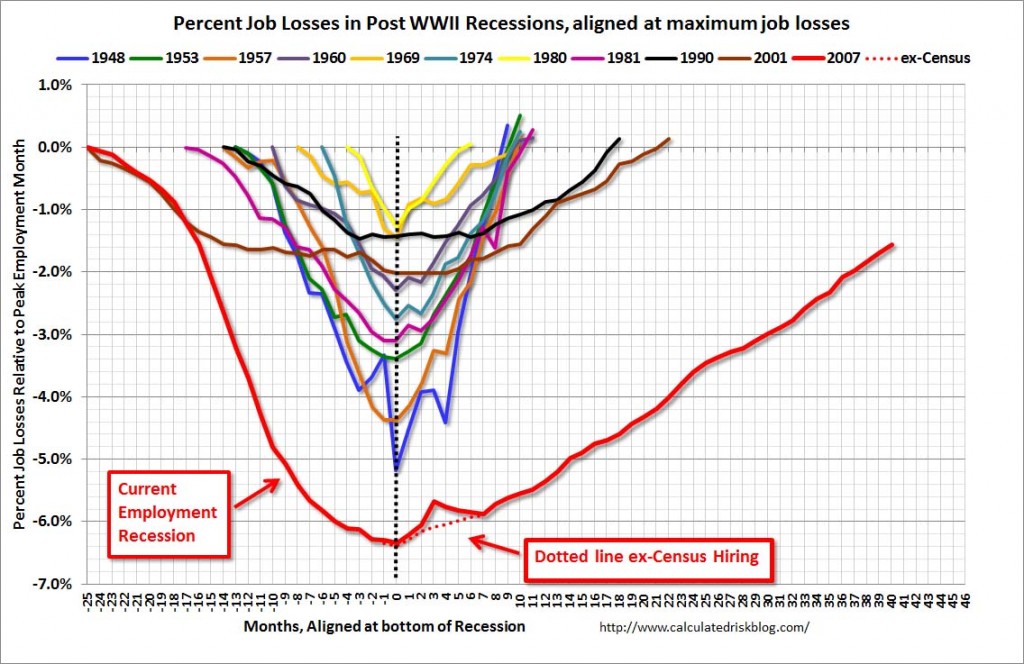

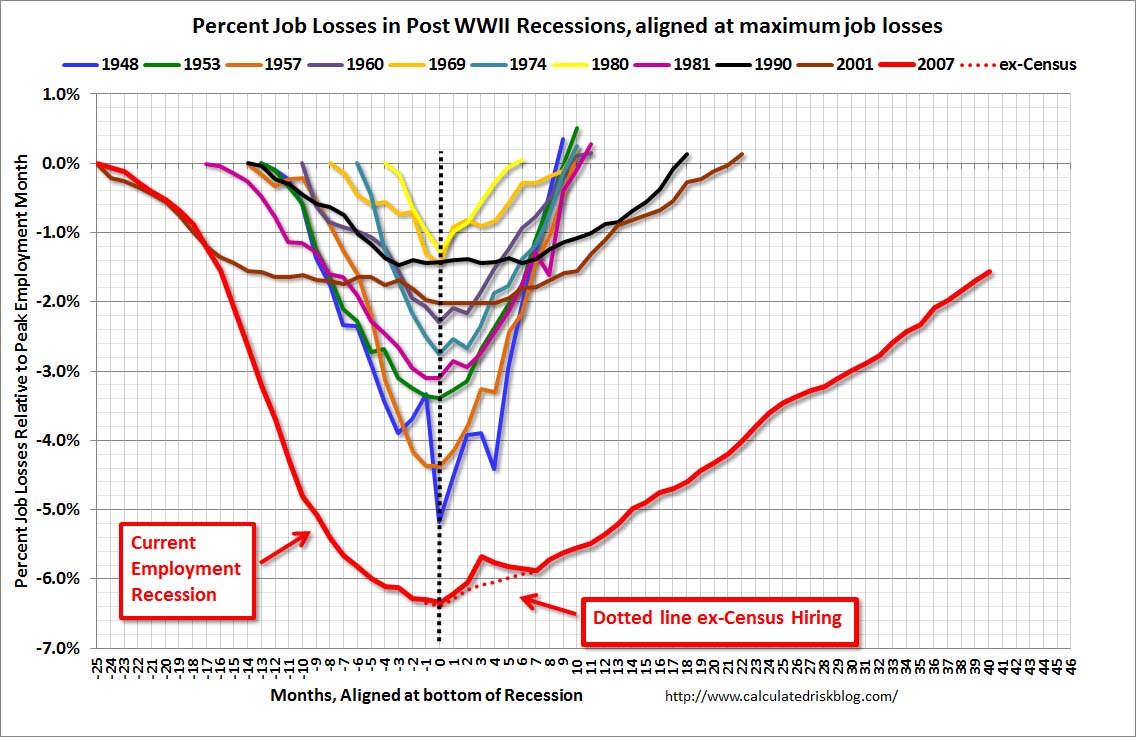

The monthly jobs report dropped last Friday, and shows a sluggish, but steady recovery. I think this chart is pretty interesting:

HT @justinwolfers for sharing that pic on Twitter, and obviously Calculated RISK Blog for posting the original.

Note how slow this recovery is, but also note that recoveries have been slowing over time – the U-shaped curves are getting more and more pronounced (less V-like) over time. This is true for the past four slumps (1981, 1990, 2001, 2007). It seems the most unique thing about the current recession isn’t just the time-to-recover, but the depth of the recession. This (admittedly very speculative) post is about the duration (and the trend to lengthening the duration in successive recessions), not the depth.

My purely qualitative theory is this: Government and industry are both mostly interested in maintaining the status quo. So, when something happens (an economic jolt, disruption, globalization) that threatens the status quo, we often must choose between letting the change happen, and trying to protect the status quo. The issue is that we often protect the status quo at the expense of economic efficiency, and this happens aggressively during recessions.

Too Big To Fail (TBTF) was a great example of this. I don’t think anyone thought, “It’s long-run economically efficient to bail these banks and creditors out.” Instead, the rhetoric was, “If we let these banks fail, our economy will crumble and who knows how long it will take to recover.” We knowingly made inefficient decisions to protect the current status quo – we weren’t willing to accept the pain of an economic correction that severe.

On his EconTalk podcast (an excellent, excellent podcast that I highly recommend), Russ Roberts frequently refers to the “Bootleggers and Baptists Theory“. Basically, bad stuff can happen when apparently-opposed interests pursue a common interest that benefits them both at the expense of society. In this case, the bootleggers were the banks, and the baptists were the politicians who (ostensibly) believed America couldn’t handle the economic fallout of allowing the banks to fail. The result was TBTF, and hundreds of billions in bailouts to banks who had already demonstrated that they were not acting in an economically efficient manner. It seems obvious to me that the banks should have failed if we’re interested in economic efficiency. They obviously didn’t operate efficiently, and the market tried to destroy them when the housing bubble popped. But rather than allow them to fail, we propped them up with tax payer dollars.

In general, we see this with rhetoric about how so and so industry is crucial to American interests, and we must protect it. The results are subsidies, favorable regulations, licensing regimes and the like. These are all essentially government and industry working together to maintain economic inefficiency for the benefit of the few, at the expense of the masses. Basically, we allocate capital (human or fiscal) to maintain the status quo rather than allowing the economy to adjust on the fly and reallocate capital efficiently. This is “sustainable” when everything is rosy – there’s all kinds of money available to maintain the inefficiency when the economy is booming. But as soon as we experience a bust, the money dries up and we can’t maintain the inefficiency because there simply isn’t enough capital.

My theory is that the more we support inefficiency is good times, the longer it will take the economy to adjust in bad times because it’s so difficult to unwind the inefficiency. The beneficiaries of the inefficiency are loathe to release the control they gain, and that control must be slowly pried away from them by economic forces over time. The more control they have, the harder it is to pry away from them. TBTF demonstrates this well: It was actually a last-ditch effort to maintain the status quo after the housing bubble burst. The “so and so industry” of the 90s and aughts was the housing industry. We put all our eggs in that basket, promoted it, lobbied for it, subsidized it, did everything we could to bolster it, ultimately misallocating a substantial amount of capital to that particular industry. When the market couldn’t bear the weight of the inefficiency, it collapsed, and the government stepped in with TBTF (a collaboration of government and industry) to try to maintain the status quo. 1 2

This all reminds me of one of my favorite E.A. Poe short stories – The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar. WARNING: SPOILERS LIE AHEAD!

The story is basically about a sick man (M. Valdemar) who is hypnotized and put into a sort of suspended state to prevent him from dying. He’s very ill and would soon die otherwise, but a “specialist” thinks he can prevent M. Valdemar from dying by putting him in a sort of hypnotic state. It works, and M. Valdemar is held there in suspended animation for a long time (like seven months). Eventually, he starts mumbling and moaning, and his caretakers/experimenters are worried something isn’t right. They decide to ask him what’s wrong. That’s where I’m picking up with the story:

“M. Valdemar, can you explain to us what are your feelings or wishes now?”

There was an instant return of the hectic circles on the cheeks; the tongue quivered, or rather rolled violently in the mouth (although the jaws and lips remained rigid as before;) and at length the same hideous voice which I have already described, broke forth:

“For God’s sake! — quick! — quick! — put me to sleep — or, quick! — waken me! — quick! — I say to you that I am dead! “

I was thoroughly unnerved, and for an instant remained undecided what to do. At first I made an endeavor to re-compose the patient; but, failing in this through total abeyance of the will, I retraced my steps and as earnestly struggled to awaken him. In this attempt I soon saw that I should be successful — or at least I soon fancied that my success would be complete — and I am sure that all in the room were prepared to see the patient awaken.

For what really occurred, however, it is quite impossible that any human being could have been prepared.

As I rapidly made the mesmeric passes, amid ejaculations of “dead! dead!” absolutely bursting from the tongue and not from the lips of the sufferer, his whole frame at once — within the space of a single minute, or even less, shrunk — crumbled — absolutely rotted away beneath my hands. Upon the bed, before that whole company, there lay a nearly liquid mass of loathsome — of detestable putrescence.

Although they found a way to maintain the status quo, suspending his death – an inefficient decision since they weren’t doing anything to actually address the causes of his illness – his body was primed to deteriorate just as it would’ve without the intervention. They managed to delay the inevitable for seven months, but once they woke him, efficiency was restored and he turned to a “nearly liquid mass of loathsome — of detestable putrescence.” At least M. Valdemar’s body was eventually allowed to correct itself very quickly. This doesn’t quite match my analogy to U.S. industry — we would’ve brought specialists, lobbyist, regulators, politicians bedside to try to slow the decay as much as possible, even after he awoke. We would’ve moved him into a freezer, or given him medicine, or whatever might work to preserve the status quo as long as possible.

So many of our economic interventions – supported by industry and politicians alike – are just like this hypnosis. They postpone the inevitable, but are ultimately bad for the economy as a whole. We hold on to economically inefficient regimes to maintain the status quo, but we’re only postponing the inevitable and misallocating resources in the interim.

FOOTNOTES: